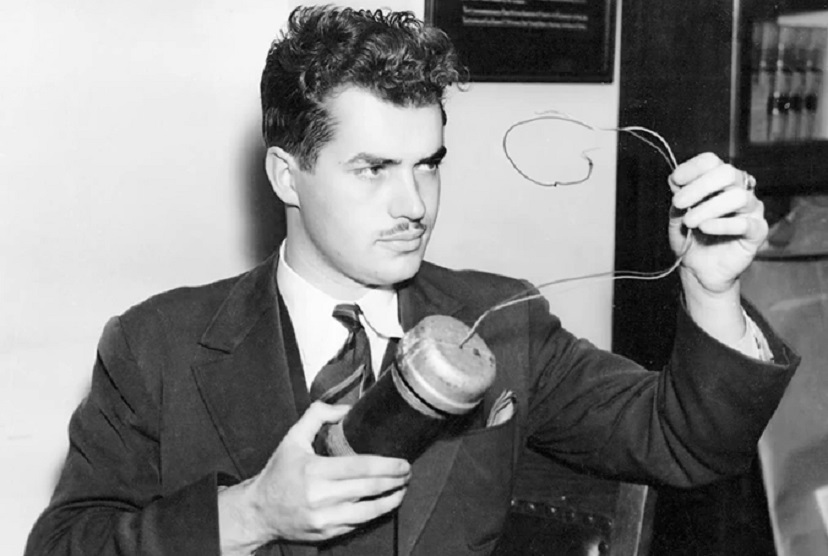

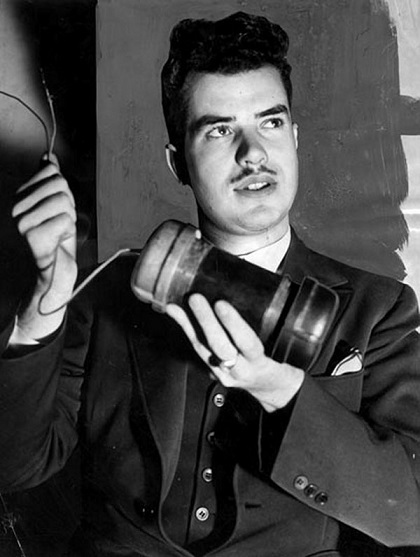

Jack Parsons at the trial of LAPD’s Earl Kynette

Jack Parsons at the trial of LAPD’s Earl Kynette

Seventy years ago Friday, on June 17, 1952, Jack Parsons—rocketry pioneer, self-proclaimed Antichrist, disciple of Aleister Crowley and explosives expert, whose work helped lead to the founding of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)—died in a mysterious, city-shaking explosion in his home lab in a converted coach house behind a mansion on Millionaire’s Row in Pasadena. Was it suicide? Murder? An accident? We still don’t know.

What we do know, however, is fascinating.

The 37-year-old’s last words were “But I’m not finished yet,” according to a report in the JPL archive. So perhaps we can rule out suicide.

The official cause is accident. But J.H. Arnold, superintendent of Bermite Powder Co. of Saugus where Parsons worked until the Friday before his death, said Parsons was “extremely safety-conscious. He worked carefully, had a thorough knowledge of his job and was scrupulously neat.” Does that mean we can rule out accident? Not definitively, of course. Police at the time claimed the explosion was the result of Parsons dropping a can of mercury fulminate, a highly sensitive explosive used as a detonator.

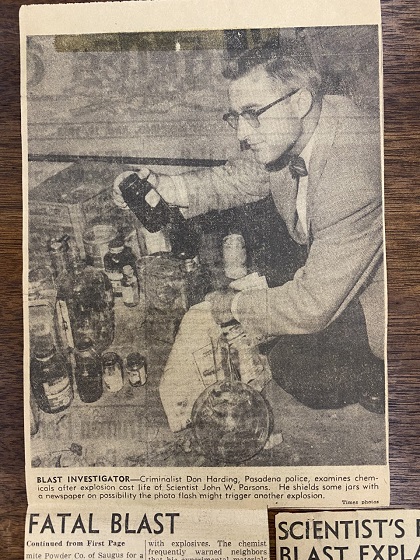

Pasadena Police chemist and criminalist Don Harding said “the quantity of fulminate of mercury could not be determined but he reported that the coffee can in which Parsons apparently was mixing the batch was shredded into shrapnel,” according to a June 19, 1952, LA Times article. “There was a large quantity of

other types of explosives in the laboratory, many of an experimental nature,” which was a violation of the Pasadena fire ordinance. “Parsons was manufacturing small quantities of the fulminate of mercury for commercial purposes.” Parsons had correctly said that “this will be my last batch.”

The JPL archive report said the Mexican government commissioned Parsons to set up an explosives factory in Mexico. He and his second wife Marjorie had been planning to leave on a trip to San Miguel, Mexico, that night or the next day, so he was transferring chemicals and explosives such as TNT, nitroglycerine, PETN and others into a trailer attached to their Packard outside. He had also recently been making pyrotechnics and special effects for motion pictures and was filling a last minute order for the Special Effects Corporation before their trip.

No final conclusions

Others have speculated that Parsons was murdered, for any number of reasons. In 1938, 23-year-old Parsons testified as an explosives expert in the trial of LAPD Capt. Earl Kynette, head of police intelligence and a corrupt cop who was convicted of placing a car bomb to blow up one of his enemies, private investigator Harry Raymond. The bomb went off but Raymond survived.

Parsons “built a bomb that he predicted closely resembled the one used in the Raymond car bombing,” author George Pendle wrote in his book Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons, which was the basis of a 2-season TV show in 2018-2019 starring Jack Reynor as Parsons on CBS+, now on Paramount+. “Accompanied by the court’s special prosecutor, he blew up an old Chrysler with it. The results of the explosion… were almost identical to those found at the Raymond site. Parsons brought a duplicate of the bomb to the stand. [It] was a persuasive piece of forensic science and a fair bit of courtroom theater.”

Parsons’ testimony helped send Kynette to prison for more than a decade, and he was released just a few days before the explosion that killed Parsons.

Marjorie believed Howard Hughes was behind Parsons’ death, perhaps to prevent industrial or trade secrets from getting out after Parsons’ recent unceremonial firing from Hughes Aviation. Or was the military worried about Parsons fleeing the country with everything he knew about rocketry and related weapons?

“I’ve never credited the ‘murder’ theories because there’s no evidence for it,” JPL historian Erik Conway said. “He was notorious for not following safety precautions with dangerous chemicals, though, and he was rushing to fill an order on a job before moving to Mexico. ‘Accident’ has always made the most sense to me.”

In the 2014 documentary “Jack Parsons: Jet-Propelled Antichrist,” Pendle said we just can’t be certain either way.

“But I think that’s just as well,” he added. “One may lean towards the accident, but I don’t think one needs to actually make any final conclusions about Parsons’ death.”

‘A very strange and tragic day in Pasadena’

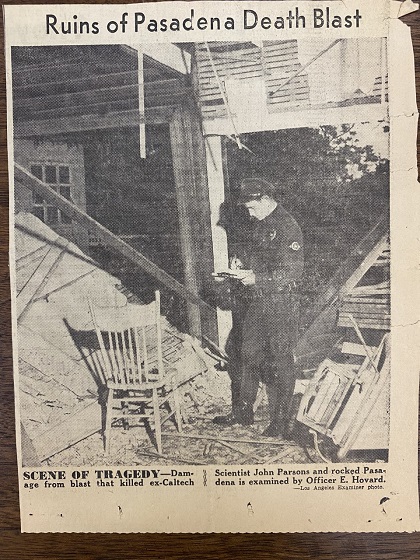

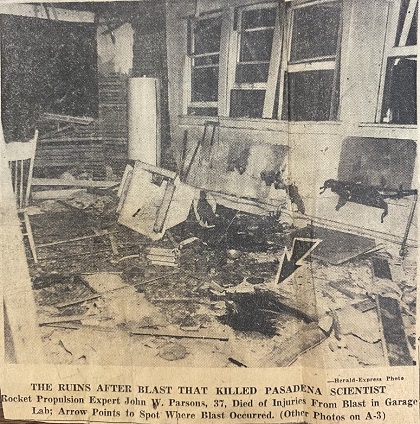

As it turned out, there were actually two explosions, according to an LA Herald-Express article the next day. Parsons’ lab was “ripped apart and a large section of the city was rocked by shock waves. One wall of the structure was blown out and the first floor was all but shattered inside.”

The blast, which occurred at 5:08 p.m. and was heard a mile away, “exploded walls outward [and] tore a hole through floor timbers.”

Fraser MacDonald, author of Escape from Earth: A Secret History of the Space Rocket, wrote that “there was a gaping aperture in the ceiling, the windows were blown out and the heavy garage doors had come off their hinges. A nearby greenhouse was floored by the blast.”

The explosion also broke the windows of a neighboring estate owned by W.W. Burris, according to a June 19, 1952, LA Times article. Several tenants were upstairs above the lab when the explosion took place. Martin Foshaug, his mother Alta, artist Sal Ganci and model Jo Anne Price were not injured, but Ganci was on the phone and was “lifted off the couch by a violent blast.” A piano collapsed and a chandelier crashed to the floor.

“Everything fell off the walls,” Ganci told the Times. “We were staggered.” Because Parsons frequently warned neighbors about the volatility of the chemicals and explosives he worked with, Ganci said he always expected “something to happen.” Ganci was the last person to see him before the explosion, telling Parsons not to “blow us up” before heading upstairs. Parsons had responded, “Don’t worry about it.”

After the explosion, Ganci saw hypodermic needles falling out of a trash can in the lab, which he got rid of before the police showed up. In another account, Harding found the needles, filled with a morphine-like substance. Parsons had taken to consuming drugs such as cocaine, morphine and peyote, much like his mentor Crowley, whom he called “father.”

“As the smoke cleared, a new layer of debris blanketed the laundry floor with fragments of plaster, splintered and distorted wood, shards of glass from windows, test tubes and the brown reagent bottles,” MacDonald wrote. “A water heater had shrunk in the corner, its pipes buckled.”

Incredibly, Parsons was still alive after the explosion, albeit missing a limb and the right side of his face. He was pinned underneath a heavy laundry tub. The other tenants pulled him free and leaned him against a wall.

“Parsons’ body was literally torn apart by the chemical blast,” reported the Pasadena Independent the next day. “The explosion blew off his right forearm, tore a gaping hole in his jaw and shattered the other arm and both legs. He was still conscious after the blast.”

He was rushed to Huntington Hospital, and the Pasadena Star-News reported that he “methodically directed his rescuers, while being loaded into the ambulance.” Officers said he attempted unsuccessfully to tell them how the explosion occurred, and died at 5:45 p.m. at the hospital.

“It was a very strange and tragic day in Pasadena,” Pendle said.

‘Criminally careless’

Harding said Parsons had been “criminally careless” in leaving explosives in the building, adding “one compound set out with the garbage was strong enough to blow up the garbage men and their truck.” In addition to traces of mercury fulminate, there were 500 grams of cordite in trash cans in the lab.

He said the explosives had been there for six months or longer and could “blow up half the block.” The Herald-Express reported that “Army Ordnance experts were summoned from Fort MacArthur to assist in the investigation and remove remaining chemicals.”

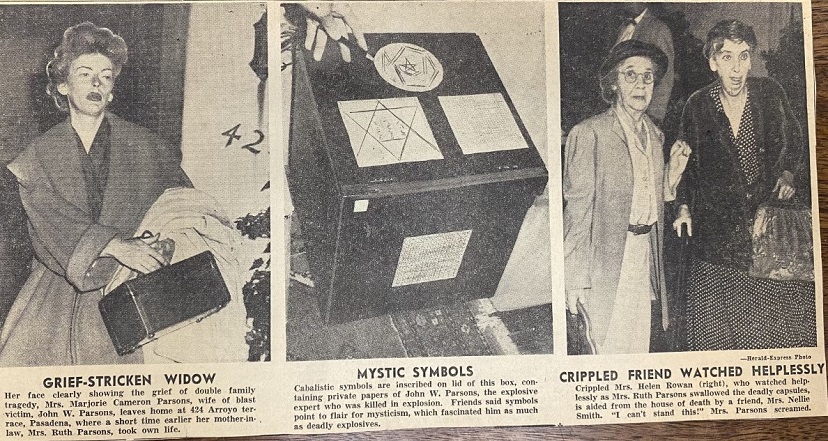

To pile tragedy on top of tragedy, Parsons’ mother Ruth, 58, killed herself at 424 Arroyo Terrace by ingesting 45 Nembutal sleeping pills just a few hours after her son died, while her arthritic friend watched helplessly, according to the LA Herald-Express. “I can’t stand it!” Ruth had cried out after learning about her son. Police shot and killed her dog when it prevented their access to the scene.

Almost immediately, some people suspected foul play in Parsons’ death. George Santmyer, a chemical engineer who worked with Parsons on a Naval Ordnance Department research project, told the LA Times on June 21, 1952, that “‘someone else’ had put quantities of explosive refuse into exposed trash and garbage containers” because it would be completely “out of character” for Parsons to handle the dangerous explosive waste material in the way police said he did.

“For Parsons to have disposed of such materials in that manner would be in the same category as for a highly trained surgeon to operate with dirty hands,” Santmyer said. “And I intimately knew Parsons as an exceptionally cautious and brilliant scientific researcher.”

He added that Parsons also would not have transported such hazardous materials in a car, especially considering he could easily acquire them in Mexico.

Harding admitted it was “incongruous,” but Detective-Lieutenant Cecil Burlingame told the Independent that “the case is closed as far as we’re concerned,” adding Santmyer’s allegation “isn’t sufficient to warrant us reopening the case.” Santmyer soon walked back his remarks, saying he wasn’t trying to imply that Parsons was murdered.

Adding to the suspicion, Harding originally said the blast “apparently occurred behind Parsons to the right. Later, he said Parsons dropped the tin and “stooped in a futile effort to grab it before it struck the floor,” and that the blast occurred at ground level. Marjorie later said the explosion came from underneath the floorboards, implying murder.

The explosion was “concentrated within a small area,” according to the Times. “Apparently Parsons received the full, terrible force directly against his body. A hole was blown through the floor directly under the section upon which Parsons presumably was standing.”

The press quickly found out about Parsons’ unorthodox beliefs and affiliations and they ran with the story. Among his luggage for the trip was a strange “black lacquer box whose lid was decorated with cabalistic symbols and which supposedly contained papers relating to his occult studies,” the Herald-Express reported. According to the JPL archive report and John Carter’s book Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons, Harding and Santmyer allegedly told amateur rocket advocate and technical bookstore employee Harold Chambers on separate occasions that home movies in the box showed Parsons having sex with his mother and her dog, though no further evidence exists.

Police told the press that Parsons’ “brilliant mind wandered into mystic fields in an unending search for a perfect way of life. He actually lived two lives. In one he probed deep into the scientific fields of speed and sound and stratosphere—and in another he sought the cosmos which man has strived throughout the ages to attain; to weld science and philosophy and religion into a Utopian existence.

“In 1942, Chief of Detectives Stanley Decker revealed, police received a letter from San Antonio, Texas. It was signed ‘A Real Soldier’ and stated a ‘black magic’ cult flourished at 1003 S. Orange Grove Ave. Detectives investigated and found the premises had been leased by Parsons” who was “interviewed and frankly told of organizing a fraternal study group to discuss ‘philosophy, religion, personal freedom and the mysteries of life and eternity.’ There were, too, studies of the pseudo-pscyhologies of fortune telling and seances.”

‘The path to a starry destiny’

Parsons’ work paved the way for rocketry as a new field of science and contributed to the founding of JPL and Aerojet Engineering Corporation. He was a self-taught rocket scientist who took some night courses in chemistry at USC for a period of time but never received a degree. And he was an explosives expert who helped develop liquid- and solid-fuel sounding rockets with a group of friends who were students at Caltech: Frank Malina, who went on to become the second director of JPL until his Communist sympathies became a problem for him in the paranoid 1950s and he moved to Paris to work for UNESCO; H.S. Tsien, a Chinese national who was deported to China due to his Communist sympathies; and Ed Forman, who was not a Caltech student but built the bodies of the rockets.

Parsons was also an occultist and disciple of Aleister Crowley, the notorious magician and leader of the Order Templi Orientis (OTO), an occultist group. Crowley, who was called “the wickedest man in the world” and called himself the Beast 666, used drugs and taboo sex in his rituals and became addicted to heroin in his later years before his death in 1947. He called his religion Thelema (Greek word for “will”). Its guiding philosophy was, “Do what thou wilt.”

“Both magic and rocketry had a basis in the imagination and in scientific method,” Pendle wrote. “What’s more, both promised to satisfy Parsons’ desire to escape the earth spiritually and physically.”

Parsons also had an unpleasant encounter with future Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, became an informant for the FBI against his rocketry partner Malina and was investigated for espionage.

A man of stark contradictions, Parsons was “almost certainly the one single individual who contributed the most to rocket science,” futurist and Discordianist Robert Anton Wilson wrote in the introduction to Sex and Rockets, written under the pseudonym John Carter because the author feared losing his government job, according to Pasadena Weekly.

Parsons’ “careful scientific experiments and theories liberated humanity from Terracentrism and showed us the path to a starry destiny,” Wilson wrote.

In the second and third parts of this series, we’ll examine Parsons’ life and legacy as it relates to rocketry and the occult.