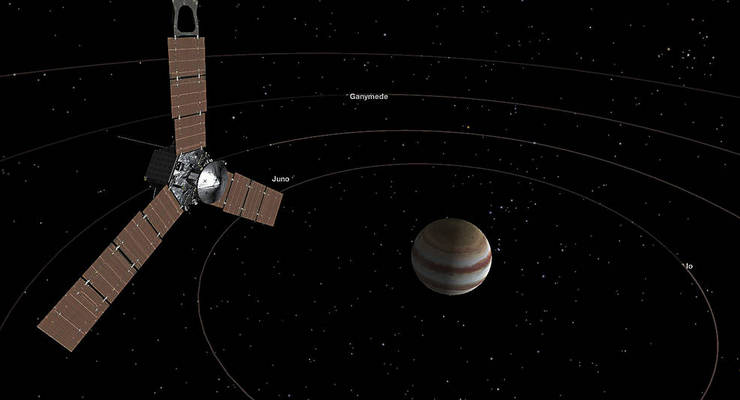

NASA has decided to extend the spacecraft Juno’s science operations until July 2021, meaning the spacecraft will have an additional 41 months to continue its orbit around Jupiter and achieve its primary science objectives.

Juno is now in 53-day orbits, instead of 14-day orbits as initially planned, because of a concern about valves on the spacecraft’s fuel system. The longer orbit means that it will take more time to collect the needed science data, a JPL statement said.

In April, an independent panel of experts confirmed that Juno is on track to achieve its science objectives and is already returning spectacular results. The Juno spacecraft and all instruments are healthy and operating nominally, the experts said.

NASA has now funded Juno through fiscal year 2022. With end of prime operations now expected in July 2021, data analysis and mission close-out activities are expected to continue into 2022, JPL said.

“With these funds, not only can the Juno team continue to answer long-standing questions about Jupiter that first fueled this exciting mission, but they’ll also investigate new scientific puzzles motivated by their discoveries thus far,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “With every additional orbit, both scientists and citizen scientists will help unveil new surprises about this distant world.”

Most recently, Juno provided scientists at JPL and NASA with data that finally solved a 39-year mystery about Jupiter’s lightning. The data showed that the origin of lightning in the planet’s atmosphere is much like Earth’s, but it also explained why Jupiter’s lightning happens mostly at the poles, instead of near the equator in the case of Earth’s.

“No matter what planet you’re on, lightning bolts act like radio transmitters – sending out radio waves when they flash across a sky,” Shannon Brown, a Juno scientist at JPL, said. “But until Juno, all the lightning signals recorded by spacecraft (such as Voyagers 1 and 2, Galileo, and Cassini) were limited to either visual detections or from the kilohertz range of the radio spectrum, despite a search for signals in the megahertz range. Many theories were offered up to explain it, but no one theory could ever get traction as the answer.”

When Juno used its Microwave Radiometer Instrument (MWR), it recorded emissions from the gas giant across a wide spectrum of frequencies, and detected about 377 lightning discharges as it flew closer to the lightning than ever before.

The new paper notes there is a lot of lightning activity near Jupiter’s poles, “which doesn’t hold true for our planet,” Brown said.

Juno will make its 13th science flyby over Jupiter’s mysterious cloud tops on July 16.

Scott Bolton, principal investigator of the Juno mission, from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, said the extension is great news for planetary exploration and for the Juno team.

“These updated plans for Juno will allow it to complete its primary science goals,” Bolton said. JPL manages the Juno mission for Scott Bolton. The mission is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. The Italian Space Agency (ASI), contributed two instruments.

For more information about Juno, visit www.nasa.gov/juno.