In August 2023, I interviewed writer and historian Michele Zack virtually for my YouTube show TRANSBRATIONS. She sat in the backyard of her Spanish-style home, and I sat in my studio in the Bronx. We discussed a range of topics, including her Canadian heritage, her dad’s 103rd birthday, and her collaboration with filmmaker Pablo Miralles on a short documentary about abolitionist Owen Brown and her work-in-progress book, Eaton’s Dilemma.

Soon enough, our conversation moved to Altadena, where we spent parts of our childhoods, albeit at different times. Zack still lives in Altadena and has since 1986.

The topic of Zack’s book, Altadena: Between Wilderness and City, came up in our conversation. It was a charming read that delved into the history of the town from its early days as a wilderness inhabited by the Gabrielino Tongva Indian tribe to the mid-1860s when Benjamin S. Eaton started developing water sources from the Arroyo Seco and Eaton Canyon, up until 2003 when The Altadena Arts Council was established. Zack’s lively depiction of Altadena’s landscape took me back to my youth when I would hike through the foothills of the San Gabriel mountains and admire Millard Falls behind the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

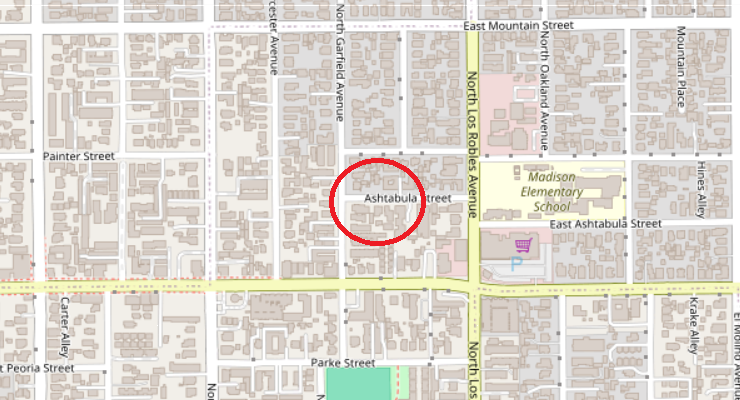

From my family’s home at Altadena Drive and Lincoln, I’d ride the 28 Bus to Don Benito Elementary School, enchanted by the landscape as we passed the canyon.

It all felt like some sort of paradise.

Zack said she had driven around Altadena to assess damage from Hurricane Hilary, which arrived on the California coast on August 21, 2023, the day of our conversation. Despite the storm being declared a major disaster and California issuing a state of emergency, Altadena was mostly unscathed. There wasn’t much damage besides rock sliding due to rain and flooding.

Then, on January 7, the news broke. Eaton Canyon was on fire. This was no Hilary.

The winds from Santa Ana blew with might and the fires raged burning everything in its path.

Images from the news showed confused elderly residents being evacuated late at night from the Terraces at Park Marino, several blocks from my mom’s home in East Pasadena.

I spoke with my mom on the phone on Jan 8. She had packed her bags in case she had to evacuate. To her relief, it seemed then, she would be OK. I alerted my childhood friend whose home was on the Westside of Altadena, four miles from the fire.

Tilly, a dear family friend, was in a completely different situation. She had worked for the California Highway Patrol in the past and had also fostered many of my cousins over the years. Tilly lived on Olive Avenue in Altadena for over fifty years and had raised three wonderful daughters. One night, my sister, maybe twelve at the time, ran to her house after jumping out of the bathroom window to escape our mother’s wrath. Throughout the nineties, I often spent time at Tilly’s during the holidays. Hers was a welcoming and pleasant home where I’d sit on her couch watching music videos on BET.

Yet, the fire was unrelenting as Tilly’s home lay in its path of destruction. Tilly and her three daughters, who all lived within walking distance of each other, lost their homes.

Two of Tilly’s daughters, Eshele and Ellen, bravely spoke out about their situation.

From Eshele: “We are now homeless and in dire need of a safe place to live. If we could receive some support, it would mean everything to us. We also pray that the rest of the Altadena community will have good fortune and prosperous futures for generations to come.”

From Ellen: “It was like something out of a nightmare – not just for my own family, but for our entire community that has been here for over fifty years. It felt like being in a war zone. My property is now just a pile of rubble, except for the metal gate that miraculously survived.”

My childhood friend, whom I initially alerted, lost his family home at Marigold near Olive Avenue. After reading online articles, I noticed my hiking buddy Randy Smith standing in front of a charred home on Woodbury Road. My friend had a look of deep anguish and devastation on his face. He was being comforted and led away by a woman. Randy’s mom, Norneice, was like an aunt, and his grandmother was like a grandmother to me and my siblings.

Donny Kincey, my former classmate at John Muir, lost his home, and so did his sister and their parents. “I really thought I could save our block,” he said. “As a palm tree lit up, it sent embers cascading into homes like bullets. The water went out and I just had to watch everything burn.”

My two childhood homes, located on Altadena Drive and West Palm Street, respectively, were destroyed by the fires. My cousin James Preston, who is eighty-nine years old, also lost two houses he owned. As time passes, I’m still finding out about classmates and community members who have also lost their homes. The latest discovery was on January 24.

Some were spared. My high school prom date’s house, Natalie Ganther, west of Lincoln Avenue, still stands. I have not received any updates about other dear friends, such as Ms. Miles on Canyon Dell Drive and Ms. Rivera on Lake Avenue. God, I hope they are safe.

I was relieved that the library on Mariposa, where I spent many hours as a youth and developed a love of reading, remains intact.

The African American community, of which me and my family are members, makes up about eighteen percent of Altadena’s population. As I reflect on the history of African Americans in both Altadena and the nation as a whole, the devastation and suffering we have endured hold even more weight and importance.

Altadena is known for its diversity and tightly-knit community environment. It has been home to well-known figures such as Charles White, actor Sidney Poitier, sci-fi writer Octavia Butler, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Jeffrey Stewart, and Rodney Glen King.

According to What’s Up Altadena?, statistically, it has the second-highest number of black-owned businesses and real estate (homes, buildings, and plots of land) per square mile in Los Angeles County. Two-thirds of the shopping centers on Lake Avenue were black-owned. Yet, seventy-three percent of those homes and businesses are now gone.

This community represents the legacy of the Great Migration in the 1920s and 1930s when African Americans left the racially oppressive conditions of the American South to find a better life in the West. They established thriving working-class and middle-class neighborhoods here. However, due to discriminatory housing practices called redlining, it wasn’t until after 1968 that they were able to fully settle throughout Altadena, primarily in the northwest section.

My grandfather Obzine Scott bought his house in Altadena in 1960. Obzine could pass for white or Latin, which might explain why he was able to purchase a home years before others.

The residential areas which were settled have been mostly destroyed by the fire.

Still, the Eaton Canyon Fire shows no bias towards race or neighborhood histories, nor does it care about my fondness for family and friends. Its only concern is consuming oxygen fueled by southern winds and destroying anything in its path.

Today, over 14,000 acres of land have burned. More than 9,000 structures have been destroyed, and over 1,000 structures are damaged. Tragically, seventeen people are confirmed dead and another twenty-four are unaccounted for. This is, by most official accounts, the most destructive natural disaster in Altadena’s history.

I know the pain of fire-related loss all too well. Twenty years ago, I lost my sister Shennea in a fire in Los Angeles. Writing her obituary was my first time expressing grief for a relative on the page. She was a part of us that we can now only access through memory.

In a New York Times article, Zack said she and her husband had evacuated and were safe, but their home, which they had painstakingly restored over decades, had been destroyed.

“I didn’t really think our house would burn,” she said, noting that it was at a lower elevation. “We packed up and left, but didn’t pack all the right things. We keep thinking of new things we lost. Why didn’t I bring out the family silver?”

I reached out to Zack to see how she was doing. She thanked me for thinking of her. I asked if she had set up a GoFundMe page. “We are okay; others are much more in need. But thanks for asking,” she replied.

I was relieved to know that Zack was safe. However, a week later, it hit me. From my home in the Bronx, New York, I could do more than donate, direct folks to resources, pray, call, worry, and offer words of sympathy to family and friends. That thought led me to plan a humanitarian mission back home to Altadena. I would rather be nowhere else during this difficult time.

The fires almost completely subsided roughly two weeks after they began.

I do hope the worst of the fires is over. Altadena will bounce back. I’m sure of this. Its diverse residents are as beautiful and resilient as its landscape. Even as they rebuild their lives and homes, the memories—joyful and comforting—of what was remains intact. Thankfully, those memories are fireproof.