Local activists were not pacified by a stipulation included in the City Council’s decision to approve the $80,000 purchase of three new automated license plate readers (ALPRs) at Monday’s City Council meeting.

In response to numerous concerns regarding privacy issues, the council asked that a condition of the purchase require that the data collected by the ALPRs will not be used in any way that violates city or Police Department policies. Further, nor will the company selling the readers, Vigilant, be allowed to sell the Pasadena data to any non-law enforcement agencies, such as insurance companies.

ALPR systems use high-speed cameras and sophisticated software to capture and convert license plate numbers into data that can immediately be compared with information in other databases.

The system can instantaneously identify a vehicle’s geographic location and the date and time the image was recorded. Police say license plate readers have helped police recover thousands of stolen vehicles.

But the system also indiscriminately collects information on millions of ordinary people going about their day-to-day business, which worries some local activists.

The cameras are placed in police cars, as well as on traffic lights, telephone poles, and even some private residences.

“What I have seen is that every time that they bring technology for surveillance, they end up using it to attack people who challenge the system, the people who disagree with people in power,” said activist Pablo Alvarado,

“I’ve seen how it’s being used to go after members of Black Lives Matter. So I hope that that’s not what the Police Department intends to do with this technology,” Alvarado said.

According to the ACLU, Vigilant, the company from which the city will purchase the cameras, sells information to CLEAR, a portal to billions of pieces of personal information.

The ACLU described CLEAR, which is a software system used by law enforcement to locate a subject’s most recent address and phone information, as well as who their associates are, as a “gateway for ICE to access the automated license plate reader database run by Vigilant.”

Mayor Terry Tornek said Monday’s action was an update of an existing program. According to Tornek, police have made a convincing case that the program is valuable in terms of solving crimes.

According to Tornek, the data is not shared, as some critics have claimed, and there are strict limitations on who can access the information. But, Tornek acknowledged that many people have a distaste for the idea that their privacy is being infringed upon and that “Big Brother” is watching and can use information in a nefarious or inappropriate way.

In George Orwell’s novel, “1984,” “Big Brother” represents the totalitarian government of Oceania, which is controlled by the Party and therefore synonymous with it.

“I get that, and that’s why we have these public discussions, and I’m glad there are advocates that are raising these questions and challenging it, so it doesn’t get out of control,”the mayor said.

Tornek maintained the city’s program is not Big Brother run amok.

“There’s always a tension between privacy advocates and people who want to make it easier to solve crimes and provide security for the population,” Tornek said. “That discussion is an ongoing discussion and the boundaries move a little bit this way and a little bit that way. One of the arguments that was made is that somehow license plates, which are tacked onto the front or rear of your car, are sort of private, and that there’s an expectation of privacy as it relates to your license plate. Given the Bluetooth technology and the tracking the private companies do of your every move, it’s laughable to pick on license plate readers as a Big Brother kind of intervention, but I’m not dismissive of it.”

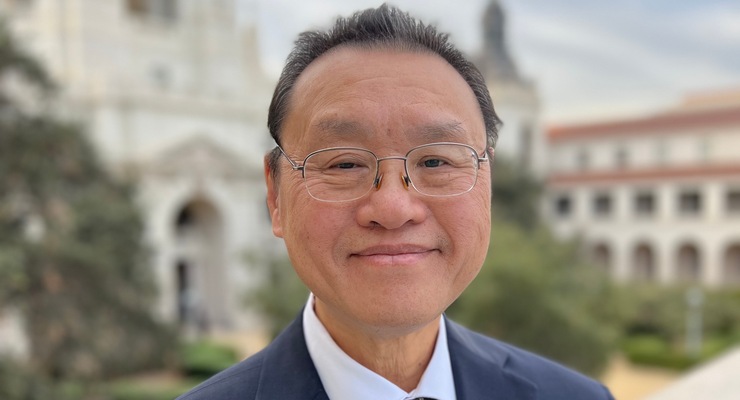

Councilman Victor Gordo, who is running against Tornek for mayor on Nov. 3, said the use of the data is important and he would not support the contract for the camera without the stipulation prohibiting reuse of the data by outside agencies or organizations.

“I’m watching carefully when the city comes back to ensure that those protections are in place,” Gordo said. “That’s why I demanded that whatever contractual agreement we enter into, those safeguards [be] in place. Those are important safeguards to everyone, all residents. I would not support this contract moving forward until safeguards on the usage of the data are in place.”

Some local advocates acknowledged the cameras could produce positive results, but they remained wary due to privacy concerns.

“As someone who is concerned about safety for all road users, automated traffic enforcement technology has the potential to reduce both racial bias and armed interactions between the public and law enforcement for traffic infractions,” said Blair Miller from the Pasadena Complete Streets Coalition. “This would be a benefit, and even more so if this technology encourages safer and slower driving.

“My concerns are over privacy and data protection. How will this data be stored, used and protected? What prevents the data from being shared with companies for money or with immigration enforcement agencies?”

Miller said he was also concerned that the technology will be employed by law enforcement within a society that has pre-existing systemic racism. For instance, which neighborhoods will they be deployed in? Or what if there is an error in the data and the wrong person gets pulled over?

Miller also cited the Aug.15 traffic stop that led to the officer-involved shooting death of Anthony McClain. The car McClain was driving in was stopped by police because it did not have a front license plate.

“Automatic license plate readers have the potential to decrease racial bias when initiating traffic stops, but we need to be very careful about how it is used and managed,” Miller said.

“We have seen with the killing of Anthony McClain how fraught traffic stops can be, for community members and for law enforcement as well. Automatic license plate readers have the potential to decrease racial bias when initiating traffic stops, but we need to be very careful about how it is used and managed.”

Larry D’Addario of the Pasadena Privacy For All Coalition said if ALPRs were limited to finding cars known to have been involved in crimes, his group would not object.

“Unfortunately, it goes much further,” D’Addario said. “ALPRs collect the number of every license plate they see, and for Pasadena’s police cars that amounts to many thousands per day. They record the time and location of every single one, not just those of stolen cars or others on a ‘hot list.’ Almost all of those cars belong to innocent residents who are under no suspicion of misdeeds. As the police cars drive around collecting all this data, they are usually not involved in investigating any particular crime. Pasadena admits that these data are saved for two years, but, in fact, they may be saved for much longer.”

The activists called for the City Council to return at a later date with a motion to end the city’s use of ALPRs.

0 comments

0 comments